Category: Uncategorized

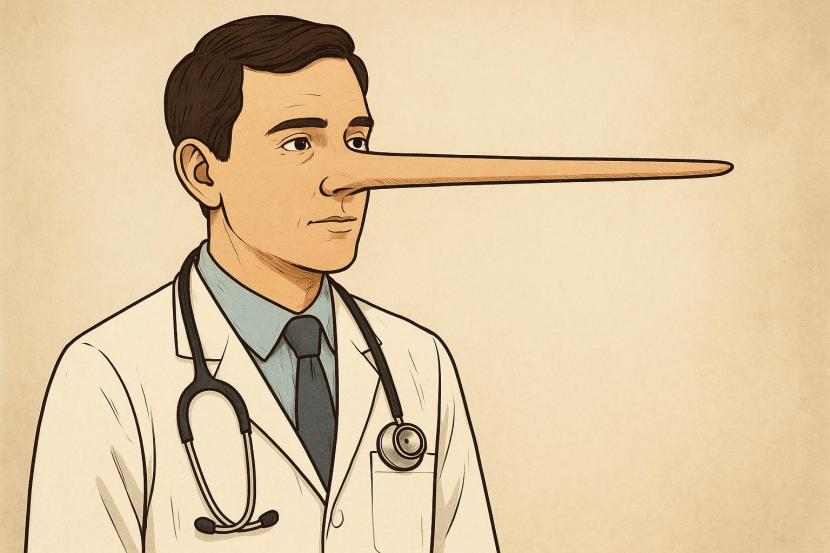

Much Ado About Personalized Medicine… or Why the Nose of Biomedical Research Keeps Growing Longer

The following article first appeared in German in the June 2025 issue of Laborjournal and was translated with the help of ChatGPT

Personalized medicine – or, as it prefers to be called these days, precision medicine (PM) – has been heralded for some time now as a kind of salvation. The great leap forward on the path to a healthier, more satisfying, and longer life. PM sounds so good, who could be against it? So convincing that it seemingly no longer needs any further proof that it represents something genuinely new – the golden road to the future of medicine.

Continue reading„Research Trek – Aufbruch in ein unbekanntes Wissenschaftssystem“

Für die Beitragsserie „Forschung vordenken für 2035“ in den table.briefings research skizzierte ich meine Vision für die wissenschaftspolitische Welt der Zukunft in Form der fiktiven TV-Serie „Research Trek“ – und lieferte die Rezension gleich mit.

Die biomedizinische Wissenschaft – grenzenlose Möglichkeiten. Wir schreiben das Jahr 2035. Dies sind die Abenteuer der akademischen Forschung, die mit ihrer interdisziplinären Crew aufbricht, die Geheimnisse des Lebens zu entschlüsseln – Krankheitsmechanismen zu verstehen, neue Diagnosen und Therapien zu entwickeln. Tief im Innersten des menschlichen Körpers und weit in den digitalen Raum hinein dringt sie vor – in molekulare Welten, die nie ein Mensch zuvor gesehen hat.

Continue readingAI in Medicine: Hubris, Hype, and Half-Science

Due to time constraints, I haven’t been able to maintain my blog since June 2023, which is why there haven’t been any new posts since then. However, the following article (published in Laborjournal 4/2023) fits very well with the last post, “Artificial Intelligence: Critique of Chatty Reasoning” and since I’ve received many requests for an English version, I asked ChatGPT (which, by the way, didn’t take offense at the content!) to provide a translation. The original German version can be found in Laborjournal.

AI has the potential to revolutionize medicine — but a reckless ‘move fast, break things’ mindset, industry lobbying, and glaring scientific gaps in transparency, validation, and bias control are getting in the way of building truly evidence-based AI.

Continue readingArtificial intelligence: Critique of chatty reasoning

Why AI is not intelligent at all, and therefore can’t speak, reason, hallucinate, or make errors

(This is a slightly extended version of my June column as “der Wissenschaftsnarr” in the German Laborjournal: “Kritik der schwätzenden Vernunft“)

The ongoing debate whether ChatGPT et al. are a blessing for mankind or the beginning of the reign of the machines is riddled with metaphors and comparisons. The products of Artificial Intelligence (AI) are “humanized“ by means of analogy: They are intelligent, learn, speak, think, reason, judge, infer decide, generalize, feel, hallucinate, are creative, (self-)conscious and make errors, are based on neuron-like structures, etc. At the same time, functions of the human brain are described using terms like computer, memory, storage, code, algorithm, and we are reminded that electric currents flow in the brain, just like in a computer. Befuddled by the astounding achievements of chatting and painting bots, many now argue that generative AI displays features of “real” intelligence, and that it is just a matter of more programming and time until AI surpasses human cognition.

The camp of those who think AI is intelligent proves its point with a long list of what AI can do that all look pretty intelligent. The doubters, however, are not convinced; they complain that AI still lacks certain “functionalities” of intelligence, following Tesler’s theorem: “AI is whatever hasn’t been done yet.”

In the following, I will argue that the current AI debate is missing the point, completely. Instead of simply marveling at AI’s putative intelligence, we should ask what intelligence, thinking, language, consciousness, etc. actually are – to measure AI against them.

Continue readingFraud in science is rare. But is this actually true?

After a break of 2 years, here again an English translation of one of the musings of the ‚Wissenschaftsnarr‘ (i.e. ‚science jester‘) – my alter ego that writes a monthly column for the German periodical Laborjournal. My apologies, to save time I used DeepL, but the AI has some difficulty with the writing style of the science jester…

Wissenschaftsnarr # 53 (German version available here)

Almost weekly we read about cases of scientific misconduct. Often, renowned journals and prominent scientists play a role in them. The website Retractionwatch by Ivan Oranski and Adam Marcus provides us with such news and their backgrounds in an incessant stream. The Laborjournal, too, has a story in almost every issue about a lab where things were not going right. Most of the time, this came to light after an article with manipulated, falsified or even invented data was exposed. Whistleblowers or attentive readers who anonymously publish their doubts about the dignity of figures on PubPeer often bring this to the attention of the scientific public. Universities, funding agencies, or journals, on the other hand, conspicuously seldom uncover such malignant machinations.

Boost your score: Digital narcissism in the competition of scientists

Do you have a fitness tracker? Are you on Twitter or Facebook and count your likes and followers? Do you know your ResearchGate score? Do you pay attention to Gault Millau toques and Michelin stars when you visit restaurants? Then you’re in good company, because you’re doing reputation management on a wide variety of levels with quantitative indicators. Just like universities and research sponsors. Except that you do it privately and entirely voluntarily!

On these pages I have recently discussed (here, and here) why in academia today we hardly judge research on the basis of its originality, quality and true scientific or societal impact. Instead, we use quantitative indicators such as Journal Impact Factor (JIF) or third-party funding, and distribute grants or academic titles based on these indicators. I also pondered a few foolish ideas on how to turn the wheel back a bit, in the direction of a content-based evaluation of research achievements. But these considerations still failed to take into account that institutions and funding agencies are in good company – namely ours – when they foster competition with simple, abstract metrics. This makes things easier for them. And at the same time, harder for us to change the system. Because we may have to change ourselves.

Continue readingJudging science by proxies Part II: Back to the future

Science gobbles up massive amounts of societal resources, not just financial ones. For academic research in particular, which is self-governing and likes to invoke the freedom of research (which in Germany is even enshrined in the constitution), this raises the question of how it allocates the resources made available to it by society. There is no natural limit to how much research can be done – but there is certainly a limit to the resources that society can and will allocate to research. So which research should be funded, which scientists should be supported?

Science gobbles up massive amounts of societal resources, not just financial ones. For academic research in particular, which is self-governing and likes to invoke the freedom of research (which in Germany is even enshrined in the constitution), this raises the question of how it allocates the resources made available to it by society. There is no natural limit to how much research can be done – but there is certainly a limit to the resources that society can and will allocate to research. So which research should be funded, which scientists should be supported?

Mechanisms for answering these questions, which are central to the academic enterprise, have evolved evolutionarily over many decades. However, these mechanisms control not only the distribution of funds among researchers and within as well as between institutions, but ultimately also the content and quality of research. The mechanisms by which research funds and tenure are evaluated and allocated and the metrics used in these processes determine scientists’ daily routines and the way they do research more than their reading literature, their views through a microscope, or their presentations at conferences. Continue reading

Science meets politics, or: Survival of the ideas that fit

Despite the fact that the number of cases is now rising sharply again and we have now entered a lockdown ‘light’, we in Germany are rightly pleased that we have so far come through the corona crisis much better than many of our neighbors or the USA. Was the ‘German way’ perhaps so successful because politicians in Germany had an open ear for science and therefore prescribed the right measures based on evidence?

Podcast mania

“The Ioannidis Affair”

On March 17th, just as many countries were taking draconian measures to contain the SARS-COV-2 pandemic, the Greek-American meta-researcher and epidemiologist John Ioannidis, whom I often quote in my posts proclaimed a “fiasco in the making‘! With strong language and a few ad hoc estimations of COVID fatality rates he warned that based on poor data or no evidence at all politicians might inflict incalculable damage on society, possibly much worse than what a virus, putatatively as dangerous as influenza, could cause. As one of the most highly cited researchers in the world and a vocal critic of quality problems in biomedicine, his COVID related interviews, opinion pieces and articles since then have received a great deal of attention, in the scientific community, in the lay press, and especially among his worldwide fan base. Continue reading

On March 17th, just as many countries were taking draconian measures to contain the SARS-COV-2 pandemic, the Greek-American meta-researcher and epidemiologist John Ioannidis, whom I often quote in my posts proclaimed a “fiasco in the making‘! With strong language and a few ad hoc estimations of COVID fatality rates he warned that based on poor data or no evidence at all politicians might inflict incalculable damage on society, possibly much worse than what a virus, putatatively as dangerous as influenza, could cause. As one of the most highly cited researchers in the world and a vocal critic of quality problems in biomedicine, his COVID related interviews, opinion pieces and articles since then have received a great deal of attention, in the scientific community, in the lay press, and especially among his worldwide fan base. Continue reading